Sand From Stones: A prologue

Word count: ~2 900 words

Content rating: PG for peril (survived through kinship and ingenuity)

First posted: October 19th, 2024

Summary: The Historian tells of his kind, the Ara. They are anthropomorphic jumping spiders, with a fruit-majority diet inspired by the real Earth spider Bagheera Kiplingi. This story tells of the cataclysm that tore apart the Ara people’s home [planet], forcing them to make the Journey of the Greatcart [through space-time]. During this exodus, the Ara made first contact with the Korvi people (feathered dragons) and their close allies, the Ferrin people (tree-dwelling mustelids).

Content information: Click here to see specific content warnings for this story.

Our stories speak of the times Before, although each storyteller shapes it differently. Such variation is to be expected after hundreds of generations; stories wear in the telling, like rocks turned smooth in the river. The stone shorn away from those rounds is carried elsewhere in the world, soon finding itself to be the sand beneath our feet. Walk on it long enough and the sand will tamp down into stone. 'Round it goes, folk say. Life rolls onward, ever changing.

Most stories agree on this much: long ago, our people awoke, and we named our kind the Ara. Our ancestors were hardly different from simple garden spiders: we were small. Fearful. Leaping for our lives at every fright, forever wasting our silk on catch-cords that got thrown away once used. It was no state for a people to live in.

Some tellers claim that there were other peoplekinds in that old world – huge ones, beastly ones. Stomping brutes who tore down forests and poisoned the sky. Other tellers merely say that the Ara were characterized by fear, back then, and they decline to mention that fear’s source.

In both versions of the tale, our ancestors already knew how to keep hidden, and how to watch carefully. With their eight eyes circling their heads, and the vibration sense of their ambiette hairs, those Ara stayed cautious. And so they endured. Observing everything around them, canting their heads in curiosity. If one does not understand, say our oldest motes of wisdom, then observe some more.

They stayed close to eltia trees for shelter. Hiding in the leaf litter, shaded by leaves above. The tree’s fruits were their blessing: easy to grab and flee with, nutritious and filling. As those Ara did that – reaching and stretching to grasp Eltia’s wholesome gifts – they began standing taller. Carrying themselves on their lower four legs, which left their upper four limbs unburdened.

The Ara had become taller – and this way, the wind spoke more clearly to their ambiette hairs. They were delighted by these wordless tales! Ara folk emerged from their safe hiding places to climb trees, cliffsides – anything to give them better vantage for the wind’s lessons. They heard tell of how joyful it felt, surging into a low-pressure space and letting oneself grow. They heard praise for the practice of rushing headlong somewhere else, like jumps chained forever in succession, curious and frightening. They heard the burgeoning anticipation of clouds gathering their rain for harvest, that vital crop that all life needed.

The Ara strained to see who was stirring up these words. Surely someone huge, and so they looked up. They searched the sky for such a being, and couldn’t find them. Observe some more, those folk must have reminded each other. They watched, searching for this speaker. And at some point, they raised their four arms – perhaps pleading for an answer. They felt the whirling air parting around their wrists, the wind’s lithe form paddled by their palms and dancing between their sensory hairs. Those Ara rejoiced, and raised their pedipalps over their heads, too. They waved all six limbs together in broad, up-down strokes of reverence.

And as those folk looked on each other’s movements of praise, each other’s grinning faces under flapping arms, they learned this as a greeting. Our foremost pair of eyes – these large ones, our maineyes – were finely honed after so much watchfulness. The Ara were able to speak sign with one another across great distances, from just-scaled heights. And this was an enlightenment! They no longer had to huddle together to hear murmured mouthwords. Despite what fears gnawed the edges of the world, they could sight another person and wave to them hello! Hello!

Those ancient kin were beginning to understand the joy of an ascending mind, and they were invigorated. The Ara gathered around their eltia trees. Over meals of fruit, they shared ideas. They learned how to dry some of Eltia’s harvest for leaner times. They started shaping the trees’ dead branches into tools, using chopping stones and growth-persuasive magics. They began building rudimentary suspension homes, fortified with vines and branches, instead of the meagre silk tents of the past. They began adding dyed silk strands to their weavings, as precursors of our many fabric patterns worn today. Those people overflowed with the desire to learn, and discuss, and create; these are the tools any thinking people need, if we are to mend the holes rent by life’s struggles.

But while the Ara people enjoyed a time of growth, the wind began changing. Blowing colder and more erratic, a call of warning. One with undertones of a magic wicked enough to pierce.

Even today, we can’t say which casting alignment that sensation likely was. Easy to blame the matter on gloamcasting, although it’s not likely fair. Most tellers hope that we never sense it again – and this historian agrees. It was surely a magic unique to the Allstorm. All accounts say that it felt like the end of times.

So those homebound Ara considered their options, watching the wind bend tall-grown trees. They considered as long as they could – and then together, as they leaped. They launched their new skills into action, wrapping themselves in silk cloth. By muffling their ambiettes against the gale, they honed their focus and quieted their fears. They then webbed together as much wood as they could gather, crafting the strongest shelters ever seen. They collected moss soaked full of drinking water. They gathered all the forms of eltia they could carry: fresh fruit, dried fruit, seeds – even four young saplings, their roots wrapped with damp straw and whispered prayers. The Ara people had shelter and provisions and a wealth of honed skill. They could hide from this weather and endure, as always, they hoped.

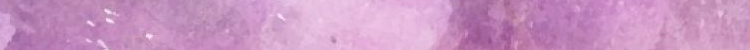

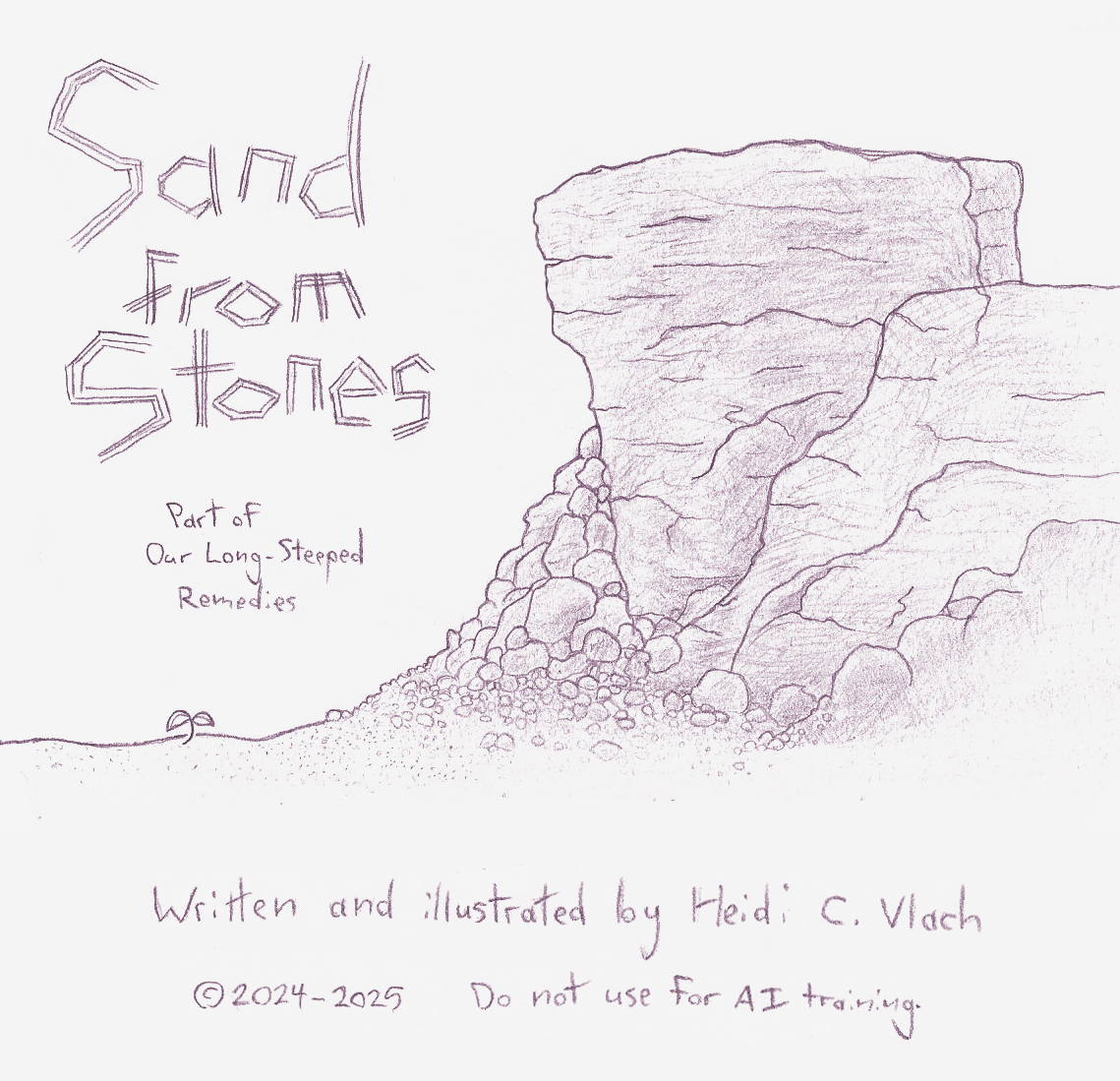

They simply couldn’t have known how severe the storm would be. The piercing sensation swelled in the air, they say. It broke through and tore the sky from its mooring, the starlight hanging in shreds and shards. The Ara shelters were enough to house everyone – barely so, fitting everyone in as tightly as jam in a crock.

But the wind was screaming of fear and flight by then. The earth shook, as the Allstorm’s dread force cleaved through the very land. Some folk near the shelter entrances tacked down silk lines and threw out balloon cords – and the wind took hold of those whipping silk lines, as though grabbing the Ara people’s outstretched hands. It seized those lines of faith, the stories say, because the shelters did lift off from the crumbling ground.

It had been many generations since the Ara were small enough to balloon on silk strings alone. The people clung to each other and to the walls of their skycarts. They wouldn’t have called them skycarts at the time, no, that’s a much younger turn of phrase. But they clung to their carts-in-the-sky, flying and falling – through what, exactly, no one can say. The Allstorm was too powerful to be understood. There were bright lights and deep gloam. Hunks of earth drifted past, torn free of their realms and leaking dazzling trails of magics. The air was thin enough to ache, some say. There was mutely howling wind and there was a hideous depth of silence.

A few Ara wriggled out of the group’s protection. They couldn’t find their dearest ones among their respective shelters’ crowds – and they were bold enough to make the leap from one shelter to another. With their silken catch-lines, they reeled the shelters all together, bundling them into a tube shape: walls made themselves of walls, forming another shelter inside. Folk spread out and breathed easier. Collaboration shared its yield, just as a watered eltia tree bears more fruit.

With enough space to work, those airborne Ara began crafting. They worked together to weave their silk into thick swaths of fabric. This they wrapped around their shelter walls, as protection from errant rock strikes, or at least a way to dampen the noise. Everyone had safe haven, then – as much as they could, at any pace.

Here, most versions of the story lose their focus once more. Some say the Ara people fell for days upon days, or perhaps longer than that. Others claim that the speaking wind returned to them amid the chaos, to whisper prophecies – or something else, perhaps. Directions. Holy signs to watch for. The strongest thread of the story is that those folk ate a little of their fresh eltia provisions, in tense moments where no one hungered much.

But every storyteller describes how the Korvi people looked to Ara eyes, when they first appeared through the murk and the mist. They were dragons, plainly enough: they resembled the little honeydrakes that visit flowers in our gardens. Two-eyed heads on long necks, single-segment bodies with two wings on the back, and thick whips for tails. These dragons were much larger than honeydrakes, though, and their feathered wings beat with a muscular ferocity that no pollinator lizard could match. Hundreds of them flew together, in a spectrum of plumage all yellow and orange and red and plum. They were forging determined through the Allstorm, evoking some shared force of will instead of merely falling. Wearing tattered clothing, and clutching precious bundles in their forelimbs – like people might.

Hello! the Ara waved to those strange folk. Could we be friends? Collaborate?

The dragons turned their slit-pupilled eyes to the Ara, and they didn’t speak – but some of the bundles they clutched in their arms did answer. Those bundles were actually small mammalian folk, waving their furred long ears like primitive pedipalps: Hello! Hello!

Here in Roundigoes, folk generally relish this part of the story. They draw their chelicerae up into fond smiles – or if they’re Korvi or Ferrin, they do the same with the muscular lips surrounding their mouths. The thought of our races meeting for the first time makes many folk mist over with sentiment.

Because those small fur-folk chattered something in mouthwords to the dragons, and the dragons swooped closer to the skycart. They set their precious companions down in the centre of the Ara shelter. Quickly, the three kinds bound themselves and their few possessions together with Ara silk. Hunks of land hurtled past; and shreds of sky in broken colours; and great orbs wreathed with fog. More stones fell onto the skycart, crashing, threatening. The dragons called out to each other. They gathered together, gripping the balloon silks that still whipped loose in tenuous space. Someone began singing a hunting song – and on that tempo, they all beat their wings as one. The shelter's momentum slowly, shudderingly changed. Rocks cascaded away in the distance. The great skycart – this Greatcart – was sailing together through all pandemonium, on dragon wings, heading no one knew where.

Eventually, the Allstorm’s force faded into the distance. The winds fell quiet. Hunks of land fell into each other, crashing and screeching, glittering with spilled magics – and the Greatcart fell, too. The dragons strained mightily but they couldn’t stop it. Everyone drifted down together, crashing into the region we now call Havenfound. Some tellers say a thicket of whitherwhere trees broke the Greatcart’s fall, or else that the thicket’s deep loam absorbed the blow. Looking at the grown-over remains of that crater, no one alive today can say for sure.

Regardless, the dragons stumbled to earth – and the long-eared speaking folk emerged from shelter. Early Ara people mistook them for rodents of some form, perhaps squirrels – but these friends of ours are ferret-kind. Slender in shape, glossy of fur, they spilled out scampering toward their dragon companions, with pleading cries. The dragons were spent from their flight, laying down leaden, heaving for breath. Ferrets scurried into action. They gripped tools and drinking skins between their teeth and ran away four-footed, vanishing into the brush with hardly a rustle. They came back with what they found: water, and medicinal herbs, and bundles of dry rushes to lay on. They attended to the dragons. Spoke to them in tones like bright music, and curled up fondly against them – as family might.

After observing that much, the Ara folk crept out of the broken Greatcart. They sat several leaps away from the dragons and ferrets; they clustered together for a shred of familiarity. And those shaken folk just looked at the sky for a long time. The lavender-flower hue of our sky was curious to them: it is said that the Ara’s lost home had a sky the colour of cobalt glass, or jay feathers, or sapphires. No piece of that came with them.

It was strangely quiet in the Landing place. The homeland we call Roundigoes had just been formed by great violence, and the wild creatures were unsettled. No warbler songs, no peeptip cries. Just trees and bushes and grasses that the Ara mostly recognized. The same types of flora as their former home, here bent under fallen stones and debris. The whitherwhere trees reached their canopies toward mauve clouds, swaying over the raw, pale sprays of splintered branches and trunks, all spread under the gently purple sky. Folk conversed in the otherkind camp nearby, piping ferret voices and sonorous dragon voices, back and forth in rhythms. There didn’t appear to be any threat remaining.

Those Ara gradually stood taller. Assessed the wind. Wrapped up one another’s injuries with silk as best they could. And, keeping a few wary eyepairs on the dragon and ferret camp, they took stock of the situation.

The Greatcart was a smashed hulk, only some of its wood and silk worth reworking into temporary tents. But the four young eltia saplings were enduring. Eltia seeds laid safely in well-padded satchels. Their dried eltia remained dry, and their remaining fresh fruit was only a little bruised from the landing. The Ara people had enough to feed everyone for a few days; they put a few eltia seeds into damp moss, so they would sprout. And then there was nothing left to be done but to have dinner.

The Ara people’s first meal in their new homeland was simple: most of their remaining fresh eltia, eaten while crouched awkward under the open sky. A few folk may have sprinkled seasonings on it, perhaps some vinegar or sugar to their preference. That’s an ordinary meal every day of the cycle. But the Ara people who landed that day did compose a charming meal recipe, in this historian’s opinion – when they made their frightened first accounts of fire-based cookery.

They watched most of the dragons recover their breath, and sit up. One dragon left – following a ferret’s chattering, pointing guidance – and they returned carrying the limp remains of a large bird the Ara had never seen before. Likely an ostroc. The other dragons heartened at the sight of it. Some of them rose, exchanged breathwords with their fellows, and helped the ferrets carry water. They partway filled their cistern, a dented metal object that they propped up on stones. The ferrets gathered dry twigs and branches, arranging them in some sort of loose stack underneath the cistern.

Someone dragonkind also unwrapped a cured leather pouch, producing a metal knife that caught the light. They cleaned and sectioned the former bird – grimly, with their two wet eyes focused on the task, and with precise movements of that fine tool. The dragon gathered up the prepared meat and the cracked bones, and dropped them, splashing, into the cistern. Other dragons gathered, speaking with growing, eager volume. They added some vegetable pluckings – lovage, greenspade, perhaps a few pungent twigs of marion. While the butcher dragon cleaned and stored their knife, another dragon got down on four limbs, inhaled deeply, and spat up something: a red plume of fire. Flames tore through the gathered wood supply, crackling hot danger licking up the cistern's round sides.

Back then, the Ara folk recoiled, trembling in fear. They didn’t know that food could be improved with a skilled application of heat: they were simply imagining their ambiette hairs catching, like so much tinder. But their maineyes couldn't look away. They saw how those small ferret people were furred, too, and yet they seemed unafraid of the flames.

No, the ferret folk were sniffing in the underbrush with their wiggling, whiskered noses, their backs turned to the luminous danger. Or else they spoke intently with each other, in a melange of mouthspeech and ear gesture. A few ferrets were even warming their small, pink hands by the fire, their fleshy fingers splayed. Or using sticks to prod at the live coals, crouched low so that their whiskers dodged the rising sparks. The dragons sat sentinel with them, occasionally stirring the cistern’s steaming mixture with a found stick of their own. Familiar tools alongside the frightening ones. Steam and smoke billowed a great hot column into the sky, but those two varieties of folk gathered underneath it didn't appear to mind.

When the mixture had bubbled a lot and it was deemed ready, the dragons and ferrets gathered with makeshift eating vessels in hand, to share portions. Some of the dragons even slurped it out of their own cupped hands, seemingly impervious to the heat. They exclaimed happily as they finished. They exhaled peals of steam through their reptilian lips, past their grinning sharp teeth.

The longer those Ara people watched, the more ferrets turned friendly ears toward them – waving more hello!s, and beckoning. Soon, the dragons joined in, waving their heavy-muscled arms over their horned heads. It was so clumsy that the Ara found laughter in it.

So they they approached. They braved the prescence of that crackling fire and accepted servings of the strange meat soup – finding it to be as richly nutritious as their own eltia. The Ara shared their food in return, teaching the dragons and ferrets how to split a ripe eltia fruit along its natural middle seam. Those folk nibbled curiously at the yellow fruitmeat, their tongues and their teeth so alien, gripping and mashing inside bone-framed mouths. Most of them seemed to like the flavour, though.

And once everyone had eaten, they dithered out how to introduce themselves in mouthwords: the dragons were called Korvi, and the small ones were Ferrin.

That was the first meal our peoplekinds ate together. First of many.

Back to top of page // Back to Heidi C. Vlach main site